Parameters Are Like Pixels

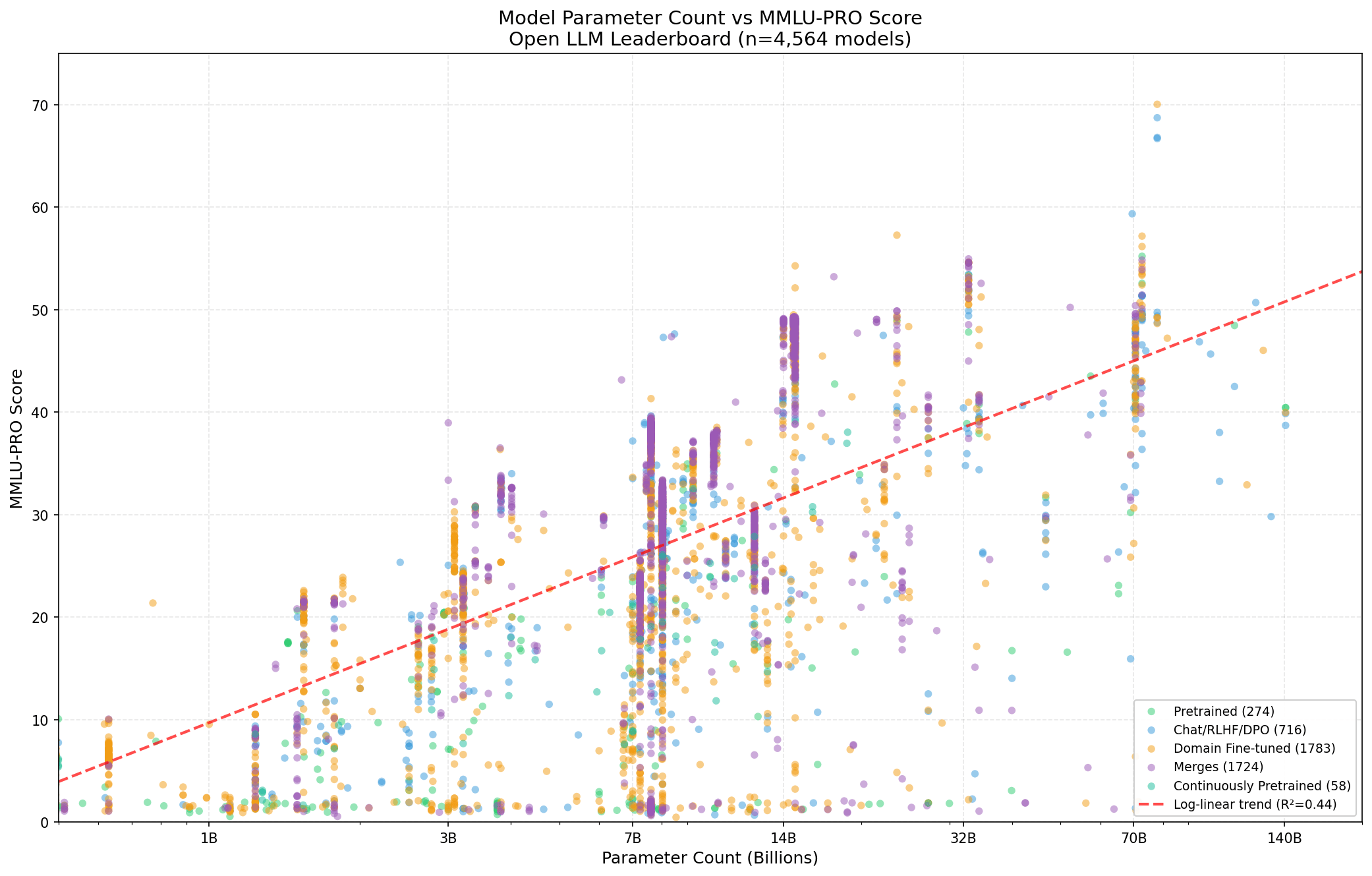

More parameters = better model. So went the common misconception. After GPT-4.5, Llama 4, Nemotron-4, and many other “big models”, I think most of you reading are already aware that the relationship between parameters and performance is not linear.

I think very few people actually have a solid intuition for what that relationship is like, though.

Chinchilla scaling laws proved that it’s not just parameter count that matters, the amount of data does, too. Textbooks Are All You Need showed that data quality is actually really important. DoReMi told us that the mixture ratios between domains (code vs. web vs. books vs. math) are important. Mixture of Experts makes it plainly obvious that we can’t even compare parameter count across architectures. And we haven’t even touched on reinforcement learning…

Yet, there is some kind of relationship between parameter count and performance. The top left of that chart is empty.

Here’s my intuition: neural network parameters are akin to pixels in an image. Images encode structure using pixels, neural nets encode structure using parameters.

More pixels/parameters means more room to encode larger and/or (at some tradeoff) more detailed structures. How you use that room is up to you.

A 100MP camera doesn’t necessarily take better pictures than one with 10MP. If your lens sucks, your optics are miscalibrated, or you’re just bad at framing an image, you’re going to get bad results.

Pixels interact in unusual ways to create structure. If you configure them right you can get a dog, or a table, or a character, or an essay, or a diagram.

Parameters are even more versatile: while pixels have enforced local relationships (which can be replicated somewhat using convolutional networks), parameters can be connected however you like. Transformers represent a generalization of those relationships, letting parameters relate differently based on context.

Neural networks use parameters to create vast latent structures of complex, sometimes fuzzy circuits. Latent space is partitioned by each activation and the parameters are used to architect impossibly vast and intricate logical structures. The complexity of those structures is directly limited by the parameter count. You can try to fit more things into a limited amount of parameters the same way you can try to fit more things into a limited amount of pixels, but you trade off clarity until the network/image eventually becomes useless.

I think this is a good way to think about parameter counts. It explains why the focus has shifted towards total compute expenditure rather than “big model good”. It gives you a frame for thinking about other machine learning concepts (if supervised learning is like taking a photograph of the dataset, what is RL?). And finally, it provides food for thought on some really interesting possibilities, like digital image editing suites for neural networks.

- omegastick